Trying Routines

Below is a list of routines and a picture of practice that describes early attempts to integrate them in classrooms as well as reflections and revisions of practice over time. The routines are listed in alphabetical order:

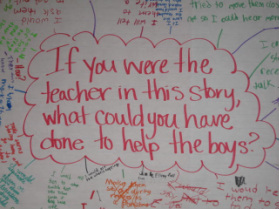

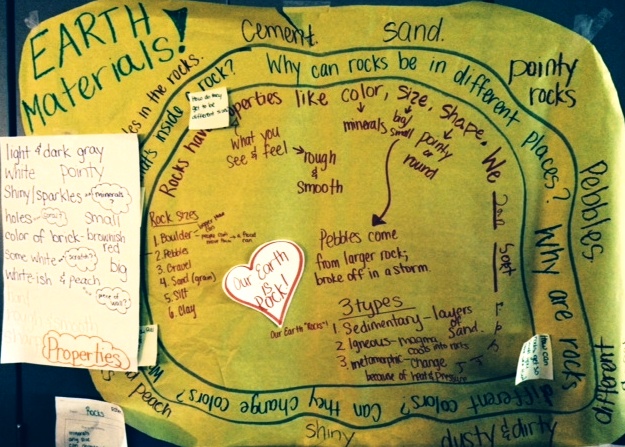

Chalk Talk

Chalk Talk has been a teacher favorite. In this routine, teachers give students a prompt and students silently (writing instruments do the talking)consider the prompt then record their thoughts and questions or comments to other students' thinking. Teachers have used it to launch units to find out student prior knowledge as well as to end units of study to provide all students an opportunity to "voice" their thoughts about concepts learned. One 5th grade student wrote her teacher a note at the end of a Chalk Talk to say, "It's a good thing because you get to write about what you think. It is quiet. Then you get to concentrate and write better."

The key to a successful Chalk Talk is a thoughtfully constructed prompt that will promote deep thinking and to debrief the responses at the end.

The key to a successful Chalk Talk is a thoughtfully constructed prompt that will promote deep thinking and to debrief the responses at the end.

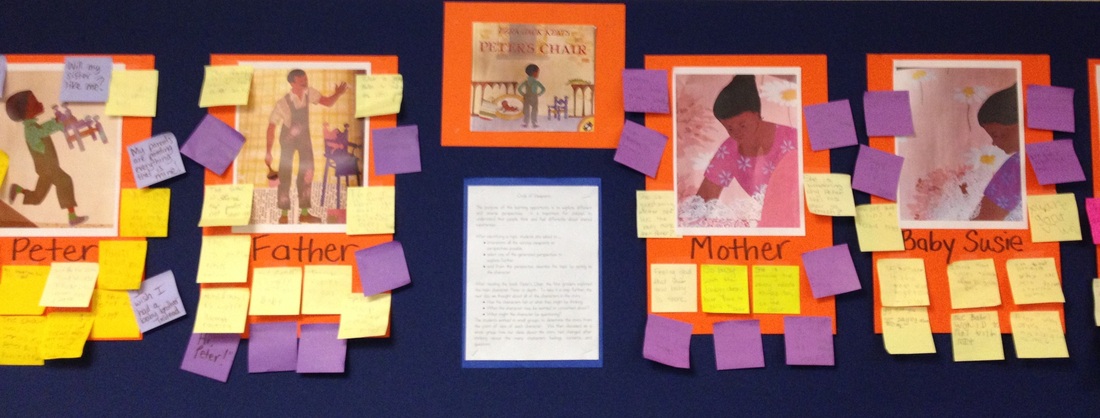

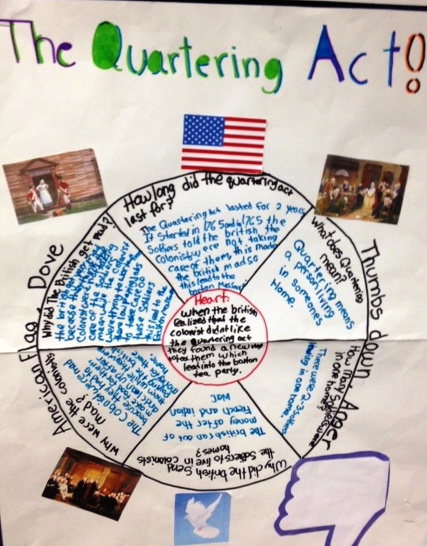

Circle of Viewpoints

Circle of Viewpoints provides a scaffold for helping students look at an issue from multiple points of view. In this routine, students become actors or actresses and take the role of the character whose viewpoint is being expressed. Being able to do this is not only a valuable life skill but it also requires students to engage multiple types of thinking such as analysis, inference and synthesis to determine what the viewpoint might be. The prompts for this routine are:

"I am thinking of (an event or issue) from the point of view of ____________________."

"I think ________________________________(this is expressed in first person, as if the

student were the character).

" A question or concern I have from this viewpoint is _____________________________"

Circle of Viewpoints is easily adapted to literature and Social Studies. First graders looked at the story "Peter's Chair" and the dilemma of the new baby from the perspective of Peter, Peter's parents and Willy the dog.

"I am thinking of (an event or issue) from the point of view of ____________________."

"I think ________________________________(this is expressed in first person, as if the

student were the character).

" A question or concern I have from this viewpoint is _____________________________"

Circle of Viewpoints is easily adapted to literature and Social Studies. First graders looked at the story "Peter's Chair" and the dilemma of the new baby from the perspective of Peter, Peter's parents and Willy the dog.

Fifth graders studied a picture similar to this from their Social Studies text then looked at the issue of slave trading from the perspective of the many different people in the picture.

To drive thinking deeper in Circle of Viewpoints, develop an overarching question that each character or personality addresses. For instance, when studying the first European explorations in Michigan, a question might be: How do racial differences affect your actions?

To drive thinking deeper in Circle of Viewpoints, develop an overarching question that each character or personality addresses. For instance, when studying the first European explorations in Michigan, a question might be: How do racial differences affect your actions?

Connect-Extend-Challenge

This has been a tough routine to teach because it really pushes student thinking as well as our own thinking. The routine is used after some type of learning has taken place. It could be a reading assignment or read aloud, a lesson in any subject or an entire unit. Students are asked to connect the new learning to something they have learned in the past, tell how the new learning has extended or changed their thinking and what still challenges them about the ideas. This could be a wondering or a statement of what they would like to learn to further extend the thinking on the subject. Here is an example: after reading about Thurgood Marshall, a 4th grade student connected the information to Martin Luther King, Jr. and how both men fought against segregation. The new information extended the student's thinking about segregation. She wrote that in spite of segregation, an African-American was still appointed to the Supreme Court which is the "highest honor a lawyer can get." The challenge was understanding why there continues to be friction between whites and African- Americans.

The challenges with this routine are: helping students understand the difference between how thinking has been extended and just simply stating a new fact. Also, it might take some effort to help students contemplate what the possibilities are for further inquiry about the subject.

The challenges with this routine are: helping students understand the difference between how thinking has been extended and just simply stating a new fact. Also, it might take some effort to help students contemplate what the possibilities are for further inquiry about the subject.

Compass Points

Teachers have been sharing with me their experiences as well as student work as they try routines in their classrooms. The very first routines used by quite a few teachers was Compass Points. They used the routine in two ways: one to find out from students what their excitement, worries, needs and suggestions were for the coming year. The second way was with parents at Curriculum night when they asked the same questions.

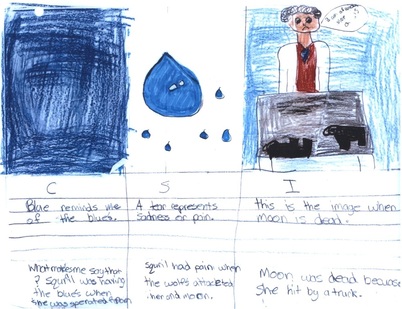

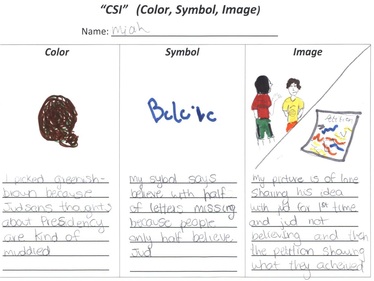

CSI (Color Symbol Image)

Fourth and fifth grade classes have done quite a few CSI projects. It can be a tricky routine because students need to include a reason why they choose the color, understand what a symbol is and then think symbolically and finally draw an entire scene. Fifth grade shared this example with me. The student is a former PACE student. Her responses show that the learning challenge she needs is built into the structure of this activity. At the same time, all students have an opportunity to stretch and show the quality of their thinking. Sometimes, results make us change our thinking about students.

Reflections and Insights:

As teachers have worked repeatedly over time with CSI, they have been finding that it is more complex, requires some frontloading and demands deeper thinking than it would initially appear. It is helpful when CSI is preceded by lessons about metaphorical thinking and/or similes. A book you might consider using for this is Quick As A Cricket by Audrey Wood. A very simple book but it gets the point across about how to consider attributes of people or things in order to think of symbolic representations . Using this routine consistently over time presents many opportunities for teachers and students to reflect together about how to stretch thinking further and further:

1. Color...Choosing a color to represent something is not hard. More daunting is telling why and what about the color makes it a good choice. Modeling and prompting over time will move students along in their elaboration on this point.

2. Symbol...There are two major factors to consider. First, students aren't always real clear about what a symbol is. Second, it is difficult for them to attribute qualities of one thing, such as a book character, to a representative symbol.

Ron Ritchhart suggests that students study the symbols on a computer keyboard to understand what it is when we talk about symbols. On a visit to Way Elementary, a Bemis teacher observed a second grade teacher post a list of math-type symbols (but these could be any symbols) that students could use in a CSI lesson. By doing this, students could simultaneously consider the picture of the symbol as well as attributes of the subject of the CSI and merge the two. Thinking symbolically is not a fully developed cognitive skill in elementary aged students so it will take time and scaffolding of learning for this understanding to grow.

3. Image... The image is the last piece of this routine, yet the most concrete. The image should be like a photograph or drawing of a scene that depicts the heart of the subject being studied for the activity. Since image is the 3rd response, students can easily just continue down the symbol path and draw something that "represents" an element in the story rather than speaks to the heart of the story. For this reason, it might be appropriate to begin this routine by asking for an image then move on to color and symbol.

As teachers have worked repeatedly over time with CSI, they have been finding that it is more complex, requires some frontloading and demands deeper thinking than it would initially appear. It is helpful when CSI is preceded by lessons about metaphorical thinking and/or similes. A book you might consider using for this is Quick As A Cricket by Audrey Wood. A very simple book but it gets the point across about how to consider attributes of people or things in order to think of symbolic representations . Using this routine consistently over time presents many opportunities for teachers and students to reflect together about how to stretch thinking further and further:

1. Color...Choosing a color to represent something is not hard. More daunting is telling why and what about the color makes it a good choice. Modeling and prompting over time will move students along in their elaboration on this point.

2. Symbol...There are two major factors to consider. First, students aren't always real clear about what a symbol is. Second, it is difficult for them to attribute qualities of one thing, such as a book character, to a representative symbol.

Ron Ritchhart suggests that students study the symbols on a computer keyboard to understand what it is when we talk about symbols. On a visit to Way Elementary, a Bemis teacher observed a second grade teacher post a list of math-type symbols (but these could be any symbols) that students could use in a CSI lesson. By doing this, students could simultaneously consider the picture of the symbol as well as attributes of the subject of the CSI and merge the two. Thinking symbolically is not a fully developed cognitive skill in elementary aged students so it will take time and scaffolding of learning for this understanding to grow.

3. Image... The image is the last piece of this routine, yet the most concrete. The image should be like a photograph or drawing of a scene that depicts the heart of the subject being studied for the activity. Since image is the 3rd response, students can easily just continue down the symbol path and draw something that "represents" an element in the story rather than speaks to the heart of the story. For this reason, it might be appropriate to begin this routine by asking for an image then move on to color and symbol.

Resources For Teaching Students How To Think Symbolically With Color

This book and song are possible resources for you to use with your class to help teach how color can be used symbolically:

My Many Colored Days by Dr. Seuss

" Colors" Song by Kira Williams (can be downloaded from iTunes.

My Many Colored Days by Dr. Seuss

" Colors" Song by Kira Williams (can be downloaded from iTunes.

For our youngest students who are developmentally still concrete thinkers, teachers can begin the metaphorical thinking process by simply linking feelings with colors. A first grade teacher told me that after reading the first pages of Arthur's Thanksgiving where he tells how nervous he is about the school play, she asked the class "What color do you think might show how Arthur felt and why?

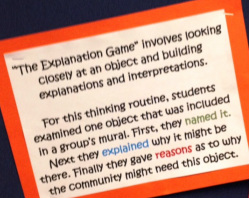

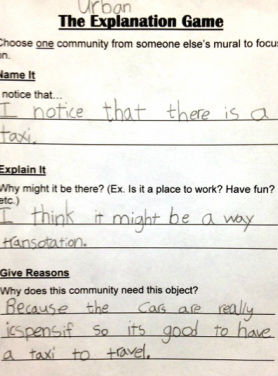

Explanation Game

There are four steps to the Explanation Game: Name it, Explain it, Give Reasons, Generate Alternatives. This routine lends itself well to math as well as other subjects. Here are 3 ways I have recently seen it used:

First Grade Math: At the end of the math unit that teaches coins and coin combinations, a first grade teacher played a shopping game with her class. Students each picked a shopping card that told what they would be buying and how much it would cost. Then they played the Explanation Game. Students had to name the amount of money they needed to spend, explain it by drawing coins to equal that amount, give reasons why that would be the correct coin combination (for example: I know a dime is 10 cents so another dime would be 20 cents and 3 pennies is 23 cents). Then they showed an alternate way to make that amount of money.

First Grade Math: At the end of the math unit that teaches coins and coin combinations, a first grade teacher played a shopping game with her class. Students each picked a shopping card that told what they would be buying and how much it would cost. Then they played the Explanation Game. Students had to name the amount of money they needed to spend, explain it by drawing coins to equal that amount, give reasons why that would be the correct coin combination (for example: I know a dime is 10 cents so another dime would be 20 cents and 3 pennies is 23 cents). Then they showed an alternate way to make that amount of money.

Fifth Grade Math: At the end of the geometry unit, students were asked to choose a shape from a collection of pattern blocks then answer these questions:

What shape do you have?

Using what you know about circles and angles, how can you figure out one angle measurement of your shape?

Using what you know about straight lines and angles, how else could you figure out one angle measurement of your shape?

Can you figure out the rest of the angle measurements in your shape? How did you figure this out? Explain in pictures.

In partnership, students had conversations and worked collaboratively with the pattern blocks to demonstrate responses to these questions.

Second Grade Social Studies Communities Unit:

What shape do you have?

Using what you know about circles and angles, how can you figure out one angle measurement of your shape?

Using what you know about straight lines and angles, how else could you figure out one angle measurement of your shape?

Can you figure out the rest of the angle measurements in your shape? How did you figure this out? Explain in pictures.

In partnership, students had conversations and worked collaboratively with the pattern blocks to demonstrate responses to these questions.

Second Grade Social Studies Communities Unit:

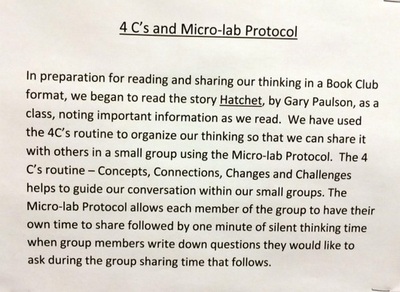

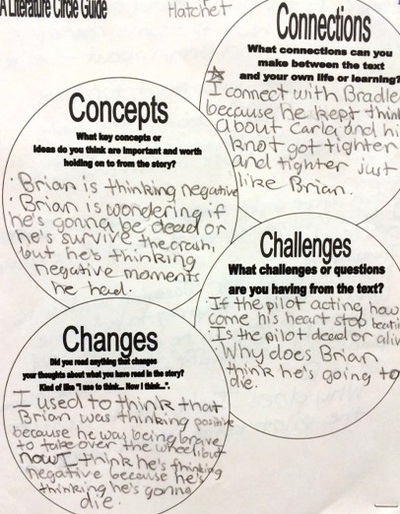

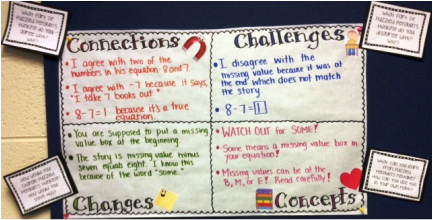

Four C's Routine and Microlab Protocol

At the district Visible Thinking Open Practice last month, teachers saw how the Four C's routine can help students organize their thoughts in preparation for student led conversations within curricula areas such as lit circles, Social Studies and math problem solving. The Four C's provides a set of questions to help guide thinking about a topic under considerations. The four C's are:

Once ideas have been recorded, students meet in small groups and reveal their thinking using the Microlab Protocol giving each student a voice. During the reflection time given at the end of each student's turn to talk, group members record questions, reflections and observations that will guide the open conversation at the end of Microlab Protocol.

A few words about Microlab Protocol...protocols in general are used to facilitate discussions in a specific manner. The primary purpose of Microlab is to allow all voices to be heard in a discussion then all ideas can be considered when the Microlab group formulates a theme or big idea that is the outcome of the discussion. Microlab Protocol procedures are described in the book Making Thinking Visible by Ritchhart, Church and Morrison. The timing suggested in this description might need to be tweaked to suit the age group of your students and the topic under discussion. More information about Microlab and other protocols can be found at

www.nsrfharmony.org

- Connections: What connections can be made with previous learning or with your life?

- Challenge: What puzzles you about this?

- Concepts: What are the key concepts or ideas worth holding on to?

- Changes: How has your thinking or attitude been changed?

Once ideas have been recorded, students meet in small groups and reveal their thinking using the Microlab Protocol giving each student a voice. During the reflection time given at the end of each student's turn to talk, group members record questions, reflections and observations that will guide the open conversation at the end of Microlab Protocol.

A few words about Microlab Protocol...protocols in general are used to facilitate discussions in a specific manner. The primary purpose of Microlab is to allow all voices to be heard in a discussion then all ideas can be considered when the Microlab group formulates a theme or big idea that is the outcome of the discussion. Microlab Protocol procedures are described in the book Making Thinking Visible by Ritchhart, Church and Morrison. The timing suggested in this description might need to be tweaked to suit the age group of your students and the topic under discussion. More information about Microlab and other protocols can be found at

www.nsrfharmony.org

We are finding that the 4 C's routine is a powerful way to frame any type of learning. A 2nd grade teacher had her class take their clipboards with the 4C's prompts to see the 5th grade science fair. The prompts motivated students to ask the 5th grade scientists questions and therefore learn more than they might have if just walking through and looking.

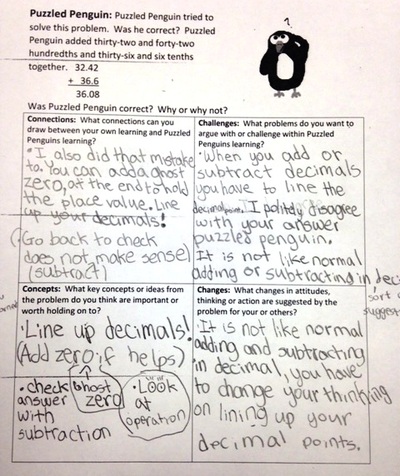

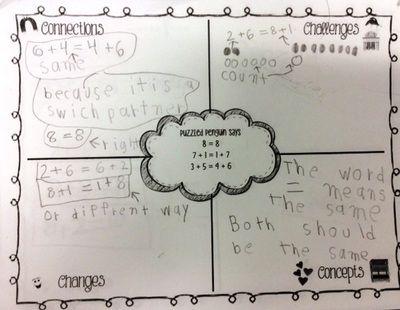

Try this routine with students when you are analyzing Puzzled Penguin in math:

Try this routine with students when you are analyzing Puzzled Penguin in math:

Another 1st grade example of using the 4 C's Routine with Puzzled Penguin.

Another 1st grade example of using the 4 C's Routine with Puzzled Penguin.

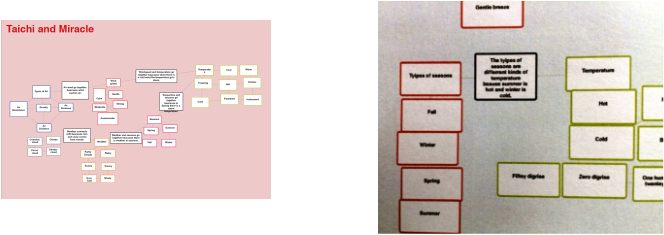

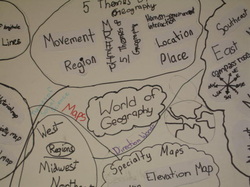

Generate, Sort, Connect, Elaborate

This routine has become a favorite to use midway or at the end of a unit because it requires students to organize learning either by sorting generated words and terms into categories or by importance to the subject. Once sorting is completed, then connections are made among the sorted words and categories and students elaborate on the concept and their learning. The competence with which students go about this task tells us how efficiently the learning has been conceptualized and allows for reteaching by helping students reorganize understanding of the subject as the task is carried out. The outcome of this routine is a concept map of student learning!

Insights and Reflections:

By analyzing where students are having difficulty with this routine, teachers can determine ways to change instructional strategies to help students build more conceptual understanding. For instance, important terms and ideas of a unit can be organized on bulletin boards or posters as the learning occurs. An example would be having a poster titled "Properties of Water" and each new property discovered through class activities could be posted. By doing this, we are helping students organize their thinking and build strong concept webs. To extend learning even further, terms and ideas of one unit web might be connected with learning in future units. In this way, students are continually making connections as well as building awareness of how thinking and understanding changes as learning continues to grow.

Insights and Reflections:

By analyzing where students are having difficulty with this routine, teachers can determine ways to change instructional strategies to help students build more conceptual understanding. For instance, important terms and ideas of a unit can be organized on bulletin boards or posters as the learning occurs. An example would be having a poster titled "Properties of Water" and each new property discovered through class activities could be posted. By doing this, we are helping students organize their thinking and build strong concept webs. To extend learning even further, terms and ideas of one unit web might be connected with learning in future units. In this way, students are continually making connections as well as building awareness of how thinking and understanding changes as learning continues to grow.

This routine can also provide differentiated learning for students. A 3rd grade teacher asked her very able students to independently generate and sort words associated with multiplication and division problem solving. She supported her struggling students in this routine by providing them with the terms and prompting them through the sort and noticing patterns at the end.

Using the Poplet iPad Ap in Second Grade Air and Weather Unit

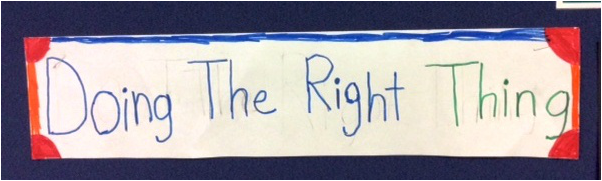

Headlines

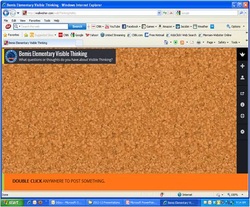

Wallwisher Board

The Headlines routine is used to synthesize learning. First attempts by students with Headlines, will typically be a fact from the learning:

Rosa Parks Refuses To Give Up Bus Seat

The intent, however, is for the headline to reflect the impact or mearning of the learning as a whole:

Rosa Parks Sits Down for Racial Equality

To help students develop this understanding of Headlines, time must be taken to study examples of headlines in newspapers and magazines and to model the thinking behind creating a headline. Once this is established, it can be a powerful way to promote deep understanding as well as a means of formative assessment.

The very nature of a headline being a short, yet powerful summary lends it to being paired with technology. Take a look at this video on Teacher Channel:

(https://www.teachingchannel.org/videos/texting-to-assess-learning)

This clip shows high school students using their cell phones to text a headline- type message to their teacher. Wallwisher.com is one website that would enable teachers to provide a similar Headline + technology experience in an elementary classroom. This website allows all students to simultaneously post thinking on a board that could be projected on the classroom Smartboard. Google Docs might also provide a format for sharing ideas through Headlines in a similar way.

Quick Tip: Have students write what made them say that on the back of their Headlines.

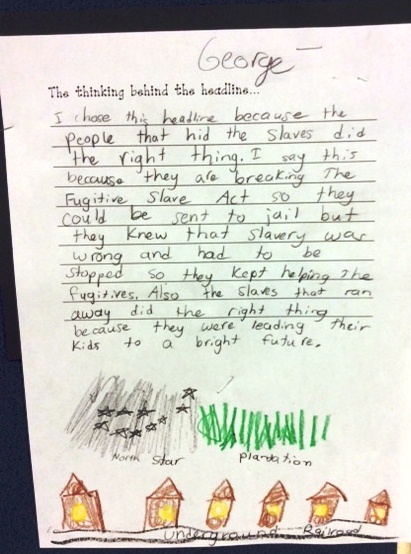

Using the Headlines Routine in 4th Grade Underground Railroad Study:

Headlines and the Thinking Behind the Headlines

Rosa Parks Refuses To Give Up Bus Seat

The intent, however, is for the headline to reflect the impact or mearning of the learning as a whole:

Rosa Parks Sits Down for Racial Equality

To help students develop this understanding of Headlines, time must be taken to study examples of headlines in newspapers and magazines and to model the thinking behind creating a headline. Once this is established, it can be a powerful way to promote deep understanding as well as a means of formative assessment.

The very nature of a headline being a short, yet powerful summary lends it to being paired with technology. Take a look at this video on Teacher Channel:

(https://www.teachingchannel.org/videos/texting-to-assess-learning)

This clip shows high school students using their cell phones to text a headline- type message to their teacher. Wallwisher.com is one website that would enable teachers to provide a similar Headline + technology experience in an elementary classroom. This website allows all students to simultaneously post thinking on a board that could be projected on the classroom Smartboard. Google Docs might also provide a format for sharing ideas through Headlines in a similar way.

Quick Tip: Have students write what made them say that on the back of their Headlines.

Using the Headlines Routine in 4th Grade Underground Railroad Study:

Headlines and the Thinking Behind the Headlines

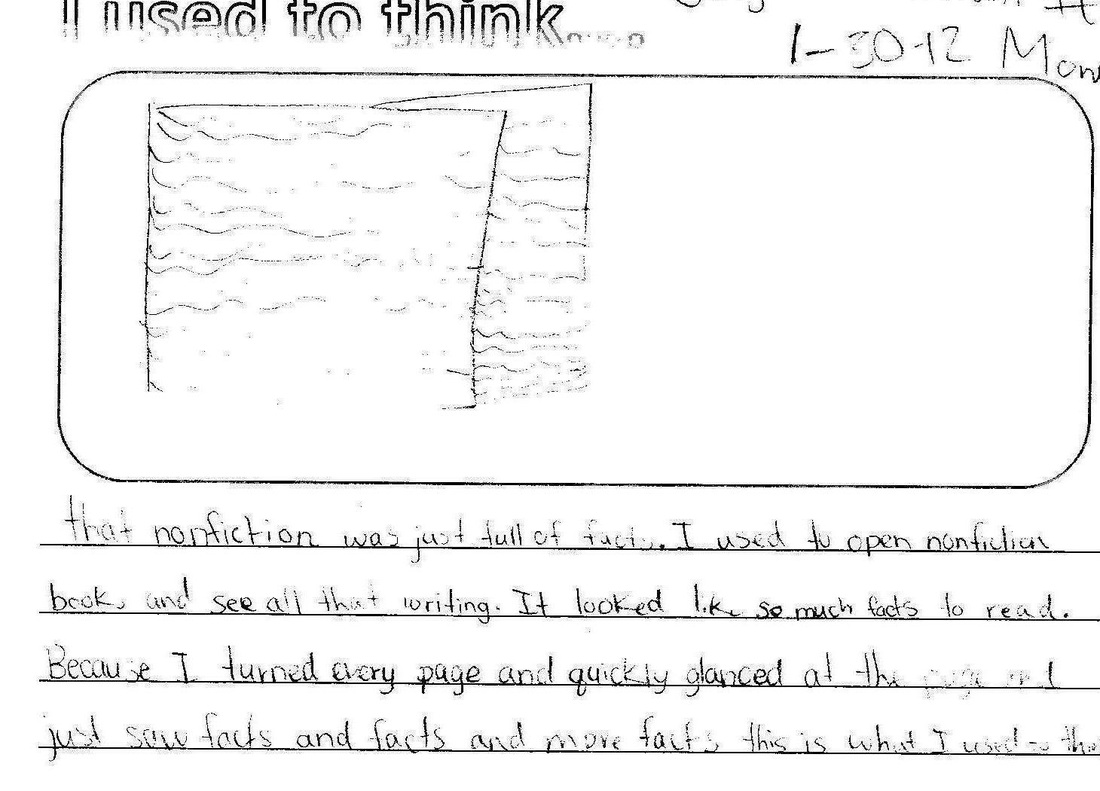

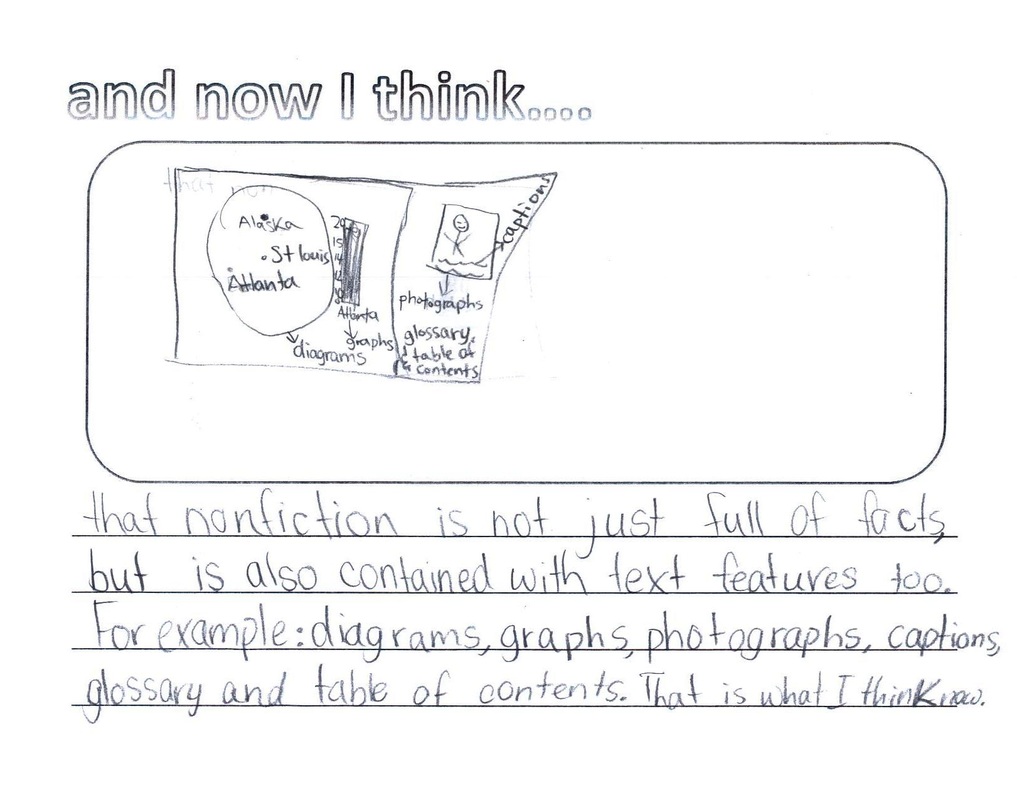

I Used To Think...Now I Think

Initially, this routine appeared to be an easy one to implement to get a quick assessment of the progression of student learning. In actuality, this routine is more complex than that.

Students often want to simply record a list of new facts learned or refute what was previously thought: "I used to think that long ago children had a lot of free time. Now I know they didn't have a lot of free time." The purpose of the routine is for students to document how thinking has changed as the result of the learning. "Now I think that children long ago had so many chores to do and had to go to bed early so they had very little free time." One solution to this is to be sure to distinguish the difference between the words know and think and model a response that demonstrates extending thinking versus telling new facts.

Another issue with I Used To Think...Now I Think is that teachers have been finding it is tricky to do this routine after learning has occurred because students have a difficult time recalling their prior thinking and the "I used to think" portion actually makes reference to new things learned. If this is a concern for you, especially in the younger grades, you might want to have students write what their thinking is about the subject before the learning occurs then give the paper back at the end of the learning for the "Now I think" response. You might want to name it: "This Is What I Think...This Is What I Think Now."

Quick Tip: If you use Think-Puzzle-Explore at the beginning of a unit, you might want to consider using the "thinks" from that as the "used to thinks" in I Used to Think-Now I Think later in the unit.

Students often want to simply record a list of new facts learned or refute what was previously thought: "I used to think that long ago children had a lot of free time. Now I know they didn't have a lot of free time." The purpose of the routine is for students to document how thinking has changed as the result of the learning. "Now I think that children long ago had so many chores to do and had to go to bed early so they had very little free time." One solution to this is to be sure to distinguish the difference between the words know and think and model a response that demonstrates extending thinking versus telling new facts.

Another issue with I Used To Think...Now I Think is that teachers have been finding it is tricky to do this routine after learning has occurred because students have a difficult time recalling their prior thinking and the "I used to think" portion actually makes reference to new things learned. If this is a concern for you, especially in the younger grades, you might want to have students write what their thinking is about the subject before the learning occurs then give the paper back at the end of the learning for the "Now I think" response. You might want to name it: "This Is What I Think...This Is What I Think Now."

Quick Tip: If you use Think-Puzzle-Explore at the beginning of a unit, you might want to consider using the "thinks" from that as the "used to thinks" in I Used to Think-Now I Think later in the unit.

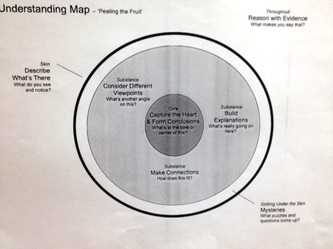

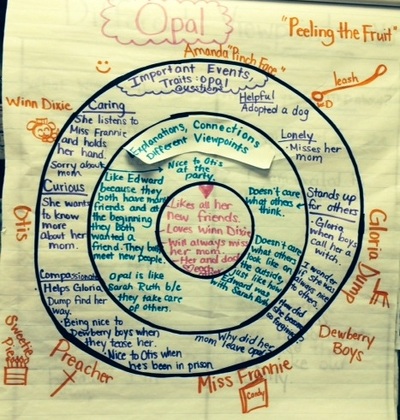

Peeling the Fruit

This is a routine that helps students organize their thinking and understanding as they study a topic. With this organizer, learning becomes analogous to cutting into a piece of fruit. The skin is the surface of the learning...what is noticeable or observable. Just under the skin are the questions and puzzles that guide the learning and may, in the end, result from the learning. The meat of the fruit represents the substance of the learning. This is where students build explanations about the learning, make connections and consider different points of view. The center of the fruit is the core that represents the heart of the learning.

Peeling the Fruit is a graphic organizer that can be used in a variety of ways to drive learning and understanding to deeper levels. The 5th grade research project (pictured below) on the American Revolution is an example of how this strategy might be used. Working in groups, students chose an event of the American Revolution. They first brainstormed examples of symbols that would be associated with the event. Next, they developed a list of questions about the event. Using the routine, Question Starts or Creative Questions, students were able to revise their lists to six "thick" questions to research. The research portion enabled students to build the substance of their learning with explanations, connections and different points of view. The research process enabled students to build a thesis which became the heart of their learning. Finally, students used this research organizer to write a five paragraph.

Peeling the Fruit can be used in small groups, with the entire class as learning progresses through a topic of study or individual students can use it to organize learning or research.

The power of Peeling the Fruit is that it is an organizer that captures the full picture of learning and keeps it visible. With this type of thinking support, students can see how all of the ideas from their learning fit together into larger concepts. Learning is less episodic and more cohesive.

Peeling the Fruit is a graphic organizer that can be used in a variety of ways to drive learning and understanding to deeper levels. The 5th grade research project (pictured below) on the American Revolution is an example of how this strategy might be used. Working in groups, students chose an event of the American Revolution. They first brainstormed examples of symbols that would be associated with the event. Next, they developed a list of questions about the event. Using the routine, Question Starts or Creative Questions, students were able to revise their lists to six "thick" questions to research. The research portion enabled students to build the substance of their learning with explanations, connections and different points of view. The research process enabled students to build a thesis which became the heart of their learning. Finally, students used this research organizer to write a five paragraph.

Peeling the Fruit can be used in small groups, with the entire class as learning progresses through a topic of study or individual students can use it to organize learning or research.

The power of Peeling the Fruit is that it is an organizer that captures the full picture of learning and keeps it visible. With this type of thinking support, students can see how all of the ideas from their learning fit together into larger concepts. Learning is less episodic and more cohesive.

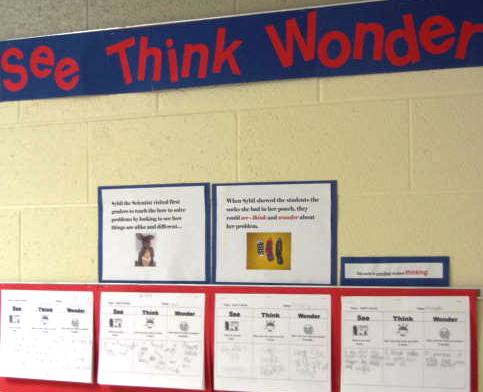

See-Think-Wonder Through New Eyes

I might guess that See-Think-Wonder has been the routine that many teachers have chosen to use in their first attempts at Visible Thinking. It makes a lot of sense. It is very close to the K-W-L strategy that we have been using for so many years. So the leap to STW wouldn't be as daunting as some of the other routines might appear to be.

At first, STW did not WOW me. Maybe that was because our first attempts were tentative and we weren't feeling comfortable with the language of the routine that elicits deeper thinking. It could also have been because we weren't selecting the context for STW carefully enough. Or perhaps it was because we still held tight reins of the instructional setting and did not release enough control to allow for dialogue among students about their thinking. Well those days are over and STW does WOW me now and this is why...

So many components of our curriculum lend themselves to STW:

Pictures in Social Studies books

Materials from the science kits

Examples of problems that reveal new math strategies

Figures and diagrams associated with different areas of math

Engaging pictures on the cover or within Making Meaning or read alouds

When we frame and guide learning with STW, we step off the stage and give students the opportunity to construct their own learning and understanding about a concept through the conversations that naturally develop as the routine is carried out. Student responses to STW have the potential to pinpoint the exact course of instruction that will meet the needs of the learners and students have the satisfaction of seeing their interests and prior understanding acknowledged. Everyone's voice is at the table because we are asking "What do you see?" and "What does that make you think?" rather than "What is the correct answer?" In short, the inquiry built into STW is powerful and takes on it's own life from class to class, subject area to subjec area and day to day as it becomes a routine in a classroom that is a Culture of Thinking.

At first, STW did not WOW me. Maybe that was because our first attempts were tentative and we weren't feeling comfortable with the language of the routine that elicits deeper thinking. It could also have been because we weren't selecting the context for STW carefully enough. Or perhaps it was because we still held tight reins of the instructional setting and did not release enough control to allow for dialogue among students about their thinking. Well those days are over and STW does WOW me now and this is why...

So many components of our curriculum lend themselves to STW:

Pictures in Social Studies books

Materials from the science kits

Examples of problems that reveal new math strategies

Figures and diagrams associated with different areas of math

Engaging pictures on the cover or within Making Meaning or read alouds

When we frame and guide learning with STW, we step off the stage and give students the opportunity to construct their own learning and understanding about a concept through the conversations that naturally develop as the routine is carried out. Student responses to STW have the potential to pinpoint the exact course of instruction that will meet the needs of the learners and students have the satisfaction of seeing their interests and prior understanding acknowledged. Everyone's voice is at the table because we are asking "What do you see?" and "What does that make you think?" rather than "What is the correct answer?" In short, the inquiry built into STW is powerful and takes on it's own life from class to class, subject area to subjec area and day to day as it becomes a routine in a classroom that is a Culture of Thinking.

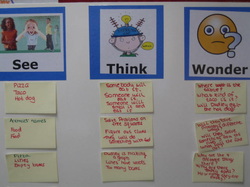

See-Think-Wonder In Action

When doing See-Think-Wonder, each student called on has the opportunity to tell what he/she sees and then you might respond: What does that make you think? or What are you thinking about that? After that, invite the student to tell: What does that make you wonder?

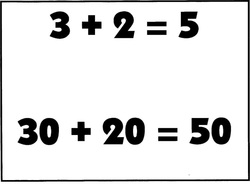

There are so many possibilities within our Everyday Math curriculum for using a visual to launch a lesson with See-Think-Wonder. Here is an example of how See-Think-Wonder might look and sound in a math lesson on place value:

Teacher: I have put some numbers on the board. What do you see?

Student: Two math problems.

Teacher: What these two problems together make you think?

Student: I think the numbers are alike?

Teacher: What does that make you wonder?

Student: Why are they so much alike?

Teacher: What does someone else see?

Student: The answers both have a 5.

Teacher: What does that make you think?

Student: 3+2=5.

Teacher: What do you wonder?

Student: What is another way that the numbers could add up to 5 in both problems?

.

Teacher: What else does someone see?

Student: Both problems have a 3, 2 and 5 but one problem also has zeros.

Teacher: What does that make you think?

Studeng: 3+2 is always 5 even if the zeros make it a different number.

Teacher: What do you wonder about that?

Student: Would it look the same if we there was a 4 and a 1?

Teacher: Let's try that? What do you see now? I wonder if there is a pattern here?

Can you imagine this going on in your classroom? The routine allows students to construct an understanding of the problem and there are many voices are at the table and many minds listening in.

There are so many possibilities within our Everyday Math curriculum for using a visual to launch a lesson with See-Think-Wonder. Here is an example of how See-Think-Wonder might look and sound in a math lesson on place value:

Teacher: I have put some numbers on the board. What do you see?

Student: Two math problems.

Teacher: What these two problems together make you think?

Student: I think the numbers are alike?

Teacher: What does that make you wonder?

Student: Why are they so much alike?

Teacher: What does someone else see?

Student: The answers both have a 5.

Teacher: What does that make you think?

Student: 3+2=5.

Teacher: What do you wonder?

Student: What is another way that the numbers could add up to 5 in both problems?

.

Teacher: What else does someone see?

Student: Both problems have a 3, 2 and 5 but one problem also has zeros.

Teacher: What does that make you think?

Studeng: 3+2 is always 5 even if the zeros make it a different number.

Teacher: What do you wonder about that?

Student: Would it look the same if we there was a 4 and a 1?

Teacher: Let's try that? What do you see now? I wonder if there is a pattern here?

Can you imagine this going on in your classroom? The routine allows students to construct an understanding of the problem and there are many voices are at the table and many minds listening in.

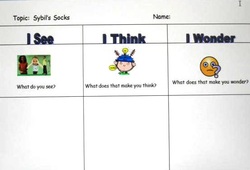

See, Think, Wonder has been used by many teachers for many purposes. Let me tell you about my experience. I have been teaching logical problem solving to first graders and have used See,Think, Wonder to engage the students to think about the elements of problem solving beyond just getting the answer.

In my first visit, I modeled the routine then had 3 students tell their responses as I recorded them. I was pleased with the thinking but wanted to make it more visible in my next lesson.

In my first visit, I modeled the routine then had 3 students tell their responses as I recorded them. I was pleased with the thinking but wanted to make it more visible in my next lesson.

For my second visit, I designed a board with more visual clues as well as more room to document thinking for all to see. I definitely noticed that students were more "in the know" about thinking and responding to the prompts, but I still wanted this to be a more thoughtful experience for all. I went back to Ron Ritchhart's explanation of the routine on the Visible Thinking Website: :(http://pzweb.harvard.edu/vt/VisibleThinking)

and found some advice I had not noticed before..."the routine works best when students use the 3 stems together at the same time...

I see.... I think... I wonder..."

So...with a goal of getting a response from every student and inspired by some work that Ashley had done with the routine , I came up with my third frame :

I am certain that after I use this for my final first grade visit, I will want to edit and redo again. Just goes to prove that launching routines is a journey!

The first grade problem solvers had many interesting responses to Dudley and Sybil's final challenge! It was clear that ongoing experience with this routine has encouraged increasingly deeper thinking. Check out some of the thinking on the wall across from my room.

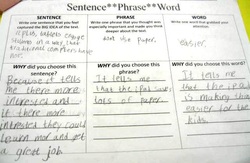

Sentence, Phrase, Word

Sentence, Phrase, Word is a routine that is text based and used for capturing the essence of the reading as well as identifying themes. It is best used with shorter pieces of text such as a chapter or article. After reading, students are asked to identify: a sentence that is meaningful to them or captures the heart of the of the reading; a phrase that spoke to them in some way; and a word that captured their attention or was powerful in some way. The power of this routine is in the justification, either through writing or discussion, about why these parts of the text stood out. Through follow-up discussion, either in small groups or as a class, students will begin to identify themes, implications and predictions leading to deeper understanding of the text.

Insights and Reflections:

This routine has worked very well with Time For Kids articles. Students struggled at first with justification for their choices, but over time they began to use words like: "When I read this part I was worried..." or "This word excites me because..." or "This phrase makes me think..." Also consider using this routine to deepen comprehension for read alouds, content area reading as well as fiction.

It is interesting to note what parts of the text are not chosen by students in this routine and that could be a springboard for another discussion.

Insights and Reflections:

This routine has worked very well with Time For Kids articles. Students struggled at first with justification for their choices, but over time they began to use words like: "When I read this part I was worried..." or "This word excites me because..." or "This phrase makes me think..." Also consider using this routine to deepen comprehension for read alouds, content area reading as well as fiction.

It is interesting to note what parts of the text are not chosen by students in this routine and that could be a springboard for another discussion.

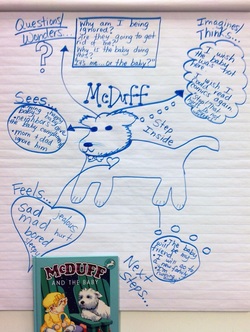

Step Inside

Bringing Voice to Step Inside

May 2014

I have been noticing that Step Insides are sounding less like a narrative with the character recounting events and feelings and more dramatic, as if the character had come to life and was acting a play. Take a look at these Step Insides from 4th grade students. They were written just before they read the ending of the novel Hatchet.

First Grade Example of Step Inside

This is a picture of the results of a Step Inside done with a first grade Making Meaning book. In the words of the teacher:

We stopped at all the parts where McDuff was upset about the baby…our biggest stopping point in the book was when McDuff was not eating…it worked out great!

We stopped at all the parts where McDuff was upset about the baby…our biggest stopping point in the book was when McDuff was not eating…it worked out great!

Step inside is a perspective taking routine. Ron Ritchhart identifies perspective taking as one of the thinking moves that leads to deeper thinking and understanding. Perspective taking presents a problem because elementary age children are still developing the cognitive maturity to step outside of themselves and take the point of view of others. So, it is necessary to scaffold student understanding this thinking move viewpoint with very concrete learning experiences.

This week, I heard of two creative ways developed by teachers to help their students understand perspective taking. The first was from a Bemis first grade teacher who realized very early in a Step Inside experience related to the class book character study was not going well and students needed some additional direction. She quickly turned the writing assignment into an acting workshop. She selected a few willing students to stand in front of the class to perform a scene from the book acting as if they were the main character. After that, all students had a chance to do some acting in small groups. The writing that resulted showed developing understanding of capturing the personality of the book characters.

The second idea came from a Barnard second grade teacher. The activity related to the study of Ruby Bridges. The teacher projected an image of Ruby on a screen and literally had the students step inside the screen image to become Ruby.

Quick Tip: If you are planning to do a Step Inside with literature avoid getting a response that is a story summary by defining one moment in the story where students will step inside. This might be at a high point in the story, at a point where a character might be facing a challenge or at the end of the story: Knowing what you know about the character, what do you think he/she might be thinking or saying or might think or say next? By framing Step Inside this way, responses will be more likely to reflect a synthesis of factual understanding about the story and character.

This week, I heard of two creative ways developed by teachers to help their students understand perspective taking. The first was from a Bemis first grade teacher who realized very early in a Step Inside experience related to the class book character study was not going well and students needed some additional direction. She quickly turned the writing assignment into an acting workshop. She selected a few willing students to stand in front of the class to perform a scene from the book acting as if they were the main character. After that, all students had a chance to do some acting in small groups. The writing that resulted showed developing understanding of capturing the personality of the book characters.

The second idea came from a Barnard second grade teacher. The activity related to the study of Ruby Bridges. The teacher projected an image of Ruby on a screen and literally had the students step inside the screen image to become Ruby.

Quick Tip: If you are planning to do a Step Inside with literature avoid getting a response that is a story summary by defining one moment in the story where students will step inside. This might be at a high point in the story, at a point where a character might be facing a challenge or at the end of the story: Knowing what you know about the character, what do you think he/she might be thinking or saying or might think or say next? By framing Step Inside this way, responses will be more likely to reflect a synthesis of factual understanding about the story and character.

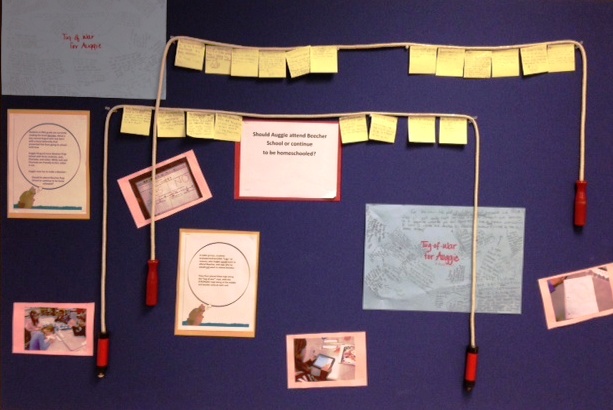

Tug of War

Tug of War is a routine for digging deeper into a subject. It can be used with curriculum as well as to gain insight into classroom social issues. The best part about this routine is, once it is established in your classroom it can be used at any moment when there are two sides to an issue that need to be explored more deeply. This is how it works:

Identify an issue with two sides

Students take a stand by generating "tugs" for each side of the issue. Every student must take a stance on both sides!

Generate reasons for each tug then rank the strength of the reasons, placing the strongest arguments at the end of the tug of war rope just as you would place the strongest participant as the anchor in a real tug of war. Then line up the rest of the tugs on each side in order of strength.

Discuss the outcome, noting any lingering questions as well as how individual thinking might have changed over the course of the exercise.

Two examples of Tug of War:

5th Grade Response to Literature:

A 5th grade class read the book Wonder by R.J. Palacio. The story is about a boy who is born with severe facial deformities and is home schooled until 5th grade when his parents begin to contemplate sending him to school. At this point in the story, the 5th grade students had a tug of war about about the questions " Should Auggie attend Beecher School or continue to be home schooled?"

Identify an issue with two sides

Students take a stand by generating "tugs" for each side of the issue. Every student must take a stance on both sides!

Generate reasons for each tug then rank the strength of the reasons, placing the strongest arguments at the end of the tug of war rope just as you would place the strongest participant as the anchor in a real tug of war. Then line up the rest of the tugs on each side in order of strength.

Discuss the outcome, noting any lingering questions as well as how individual thinking might have changed over the course of the exercise.

Two examples of Tug of War:

5th Grade Response to Literature:

A 5th grade class read the book Wonder by R.J. Palacio. The story is about a boy who is born with severe facial deformities and is home schooled until 5th grade when his parents begin to contemplate sending him to school. At this point in the story, the 5th grade students had a tug of war about about the questions " Should Auggie attend Beecher School or continue to be home schooled?"

1st Grade Tug of War

Should the Gingerbread Man have run away from home or not?

Should the Gingerbread Man have run away from home or not?

It 's the end of the first marking period, MEAPs are over and teachers are feeling like they aren't juggling so many balls at the same time. So there seems to be a lot more Visible Thinking buzz and activity. Consequently, my list of new topics for this website/blog is growing and it was very hard to choose which to write about this week. The idea I finally settled on came from a PLC meeting I attended at Barnard this week where the staff learned three Visible Thinking Routines. One of the routines was "What Makes You Say That?" This may be the simplest way of all for you to unpack your students' thinking. It takes discussion and thinking beyond surface level and can easily slip into day to day and subject to subject teaching. By following- up with the prompts "What do you see that makes you say that?" or "What do you know that makes you say that?" it may help students determine the evidence or support for their statement. By using this routine, you show students that you value their thinking and give them many opportunities for students to share it thinking and make it visible.

The "What Makes You Say That?" poster was designed by the art teacher at Costello and Bemis. The many different question marks represent the many different points of view the question might provoke. If you would like a copy for your room, let me know and I will send it to you as an email attachment.

The "What Makes You Say That?" poster was designed by the art teacher at Costello and Bemis. The many different question marks represent the many different points of view the question might provoke. If you would like a copy for your room, let me know and I will send it to you as an email attachment.

Zoom-In

Zoom-In is a variation of See-Think-Wonder in that it asks students to attend to detail. In this version, students are asked to make sense of a picture or diagram as parts are slowly revealed. It helps students access prior knowledge and build new learning. I have seen it used very successfully to introduce new math concepts where attention to patterning and detail would be important for devleoping new understanding.

A well chosen photo or diagram can also be used to introduce a new unit. It gives students an opportunity to begin building understanding of new learning through pictures. I recently worked with second grade teachers to develop an introductory lesson for the Balance and Motion science unit. It took a few tries to refine it, but we had success using a picture of someone walking a tight rope. By slowly revealing parts of the picture starting with the top, students focused in on the balance bar being used by the rope walker and that was the launch toward the discoveries that will be made throughout the unit.

It is easy to put together the picture prompt for Zoom-In on your Smartboard by using the shade to cover then reveal picture parts. Another method is to put a picture on a PowerPoint slide then cover it with a rectangle from the shapes menu. The rectangle can be moved up or down either with the computer cursor or by grabbing it on the Smartboard.

When doing Zoom In, remind students that it is not a guessing game but rather a thoughtful observation. Also, it is a routine that should be done verbally so everyone might hear the thinking of others and extend their own thinking from what they are hearing.

Here are some prompts that might be used as each portion of the visual is revealed:

A well chosen photo or diagram can also be used to introduce a new unit. It gives students an opportunity to begin building understanding of new learning through pictures. I recently worked with second grade teachers to develop an introductory lesson for the Balance and Motion science unit. It took a few tries to refine it, but we had success using a picture of someone walking a tight rope. By slowly revealing parts of the picture starting with the top, students focused in on the balance bar being used by the rope walker and that was the launch toward the discoveries that will be made throughout the unit.

It is easy to put together the picture prompt for Zoom-In on your Smartboard by using the shade to cover then reveal picture parts. Another method is to put a picture on a PowerPoint slide then cover it with a rectangle from the shapes menu. The rectangle can be moved up or down either with the computer cursor or by grabbing it on the Smartboard.

When doing Zoom In, remind students that it is not a guessing game but rather a thoughtful observation. Also, it is a routine that should be done verbally so everyone might hear the thinking of others and extend their own thinking from what they are hearing.

Here are some prompts that might be used as each portion of the visual is revealed:

- What do you notice in the picture?

- What does that make you think?

- What do you think might be in the rest of the picture?

- What has changed in the picture?

- What is the feeling or mood?

- How has the feeling or mood changed?

- Imagine how the rest of this picture might look.